Are you curious about the scientific marvels that shape our world? Are you intrigued by the dance of light and matter that fuels technological progress? If so, we have a treat in store for you.

Tapered Fibers

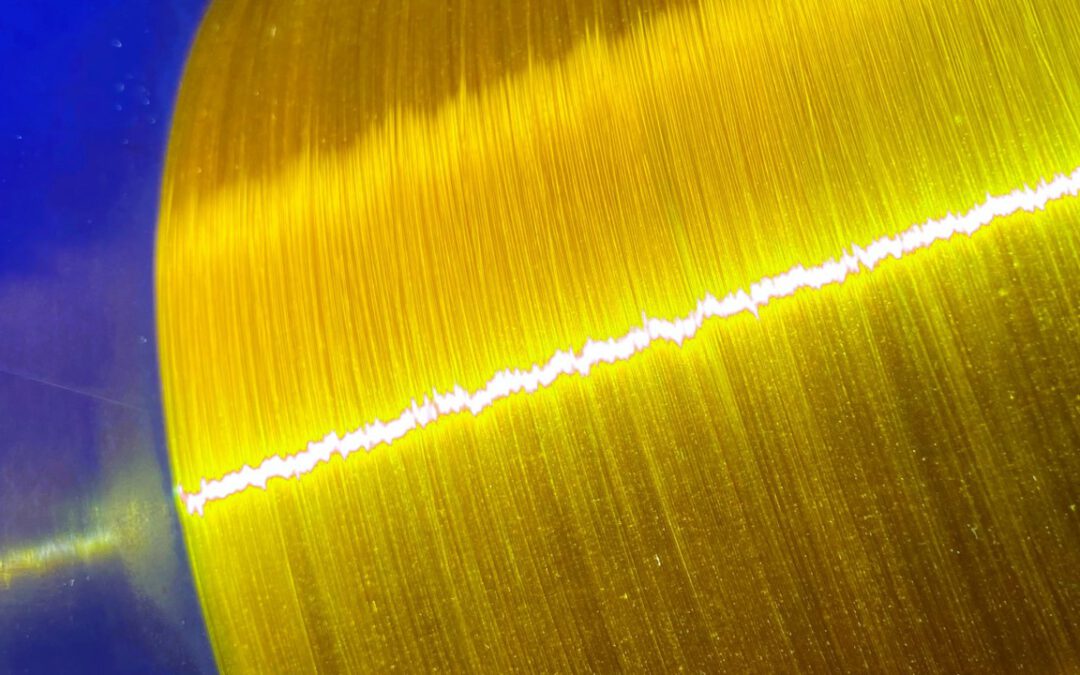

In the vast realm of photonics, where light dances and communicates, a seemingly unassuming innovation has captured the imagination of researchers and engineers alike: tapered optical fibers. With their gradually diminishing diameters, these slender wonders possess the power to revolutionize sensing, telecommunications, and nonlinear optics. In this article, we embark on a journey through tapered optical fibers, exploring their physics, applications, and the mathematical underpinnings that make them so fascinating.

The Physics Behind Tapered Fibers

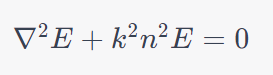

The wave equation can describe the behavior of light in a tapered fiber:

where:

- E is the electric field amplitude.

- k is the wave number (k=2π/λ, where λ is the wavelength of light).

- n is the refractive index of the fiber core.

At the heart of a tapered optical fiber lies the interplay of light and matter. The wave equation governs the behavior of light within these fibers, with E representing the electric field amplitude, k as the wave number (k=2π/λ, where λ is the wavelength), and n as the refractive index of the fiber core. By manipulating these factors, researchers can craft fibers with unique light-guiding properties.

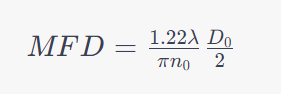

The tapering process itself is a delicate art. Techniques like heat stretching and chemical etching transform an ordinary fiber into a tapered one. As the diameter narrows along the fiber’s length, light experiences enhanced confinement within the core. The mode field diameter (MFD), describing how light spreads within the fiber, reduces, leading to intensified light detention.

Mathematics in Tapered Fiber Design

The key to understanding tapered fibers‘ behavior lies in mathematics. Consider a Gaussian mode profile with an initial diameter of D0 and a refractive index n0. The MFD can be approximated as follows:

Applications and Light Transmission

Sensing: Tapered fibers are excellent sensors due to their ability to detect environmental changes. When light interacts with the external medium, the evanescent field, which extends beyond the core, plays a crucial role. Changes in temperature, pressure, or refractive index lead to alterations in the evanescent field, offering a sensitive means of detection.

Telecommunications: Tapered fibers facilitate efficient light coupling between different fibers or components. By matching mode field diameters, they improve coupling efficiency and minimize losses.

Nonlinear Optics: The small core diameter of tapered fibers intensifies nonlinear optical effects like four-wave mixing and supercontinuum generation. These effects are instrumental in generating new frequencies of light and manipulating light in advanced optical devices.

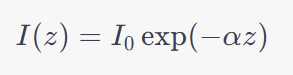

Light Attenuation and Transmission

Tapered fibers‘ impact on light attenuation and transmission cannot be overstated. Various factors contribute to attenuation, including absorption, scattering, and bending losses.

Absorption Loss: When the fiber’s material absorbs light energy, it’s converted into other forms of energy, usually heat. The intensity I of light after propagating a distance z can be described as I(z)=I0 exp(−αz), where α is the absorption coefficient.

Scattering Loss: Irregularities in the fiber’s material scatter light, contributing to scattering loss. The intensity I after propagating a distance z can be approximated as I(z)=I0 exp(−βz), with β being the scattering coefficient.

Bending Loss: Bending the fiber leads to energy leakage due to the curved geometry. Bending loss depends on the bend’s curvature and the fiber’s properties.

Total Attenuation: The total attenuation αtotal encompasses absorption, scattering, and bending losses: αtotal =α+β+αbend.

Unveiling the Possibilities

Tapered optical fibers are far from mundane threads of glass. They are gateways to innovation, where light and matter harmonize unexpectedly. The gradual tapering, guided by mathematical principles, unlocks unprecedented opportunities.

As researchers continue to explore the realm of tapered optical fibers, their applications burgeon. The possibilities are limitless, from the precise detection of minute environmental changes to the blazing speeds of information transmission. Tapered fibers pave the way for more compact, efficient, and versatile optical devices, promising a brighter, more connected future.

Tapered optical fibers, born from meticulous craftsmanship and mathematical insight, are a testament to the marvels of photonics. These fibers redefine light’s journey, transforming mundane optical communication into a symphony of interactions. As we venture further into the age of light, let us remember that even the most diminutive innovations can carry the power to illuminate the world.

Please note that the provided equations are simplified and may only account for some possible factors. Actual attenuation behavior can be more complex and require more sophisticated models for accurate predictions.